Produced and edited by Miranda Shafer

Once upon a time, when we were very little there was 100 Acre Wood where we would toddle about with Pooh and piglet learning lessons on friendship and kindness. A few years later we would stumble across the singing flower garden with Alice before arriving at the Queen’s treacherous red rose beds.

Mary Lennox would call to us from the pages of The Secret Garden pushing aside the ivy and overgrowth to discover something beautiful and full of our greatest desire – potential.

Older still we found ourselves at the mercy of Narnia where the forces of Good and Evil could be easily understood by the effect they had on the landscape of that magical world.

At the bloom of adolescence, we discovered love and lust in the blossoming Night Garden of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

We are creatures conditioned to find ourselves in Flora. We’ve learned our earliest life lessons through walks in literary Gardens.

But what of later life? What blooms when we start to fade? Where’s the story to guide us through loss, disappointment, infidelity, anger, fear, and defeat?

How do we move through the garden of adulthood without parables to lead the way?

Now what if I told you that Garden existed. And what if I told you, it was not in the yellowing pages of a dearly loved book but in the here and now. A living breathing place built to process the complex and competing emotions of adulthood.

I’m Hilarie Burton Morgan, and this this is A Walk in Wethersfield.

The Hudson Valley lies two hours north of Manhattan. It has benefited from the wealth and resources the city provides – while maintaining a roguish sense of rural stubbornness.

With fertile ground and postcard-perfect seasons it is a place where man can make his agricultural mark – and just as easily, Mother Nature can take it back.

That constant push and pull has existed here for centuries. The balance of order and chaos, control, and reckless abandon.

The Hudson Valley of the early 20th century was not all that different from the state in which it exists today. The roads are still winding. The sunrises and sunsets are still heart-stopping in their orange and pink and lavender extravagance. The old growth trees still lean conspiratorially together. Main streets are still sleepy but proud. A Rip Van Winkle timelessness has permeated the valley.

The raw beauty of this place was studied and captured masterfully during the mid-1800s during the height of the Hudson River School of painting. These artists idolized the nature of this region and saw its beauty as a reflection of God.

A few decades later a child was born who very much took that sentiment to heart. The combination of art and nature was a religious experience.

The Hudson Valley holds its secrets close. And so, before we can tell you where this garden hides, it is imperative to tell you who built it.

Chauncey Stillman. Now without knowing a thing about this man, it is a name that implies wealth, privilege – like something out of an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel. It would be easy to make such assumptions and certainly a number of them would be correct.

But. There is more to this child of the Gilded Age than Society pages of the era would report.

HB: I think it’s worth noting up front that you and I have been friends for a very long time – and we were friends for a very long time before you ever mentioned Wethersfield to me. You would talk randomly about, ‘oh my grandfather’s house,’ and I imagined just, you know, a farmhouse. Why do you think you hold Wethersfield so close?

TS: It is difficult to describe. It’s complicated to me. It is this beautiful presence, a memory.

In my life it represented different things at different times. And so, I’ve had to kind of figure out the way to make it real and relevant – while holding it deep, deep in memory that allows me to remember what it was. And allows me to make it what it could be now.

HB: Let’s get into a little bit of your family history. Because again, we were friends for years before you told me about your family history. As an outside observer I find this kind of stuff fascinating. We watch movies, we watch TV shows – The Gilded Age is coming out. We are fascinated in the legends of America – the people who built America. And your family really played a strong role in that.

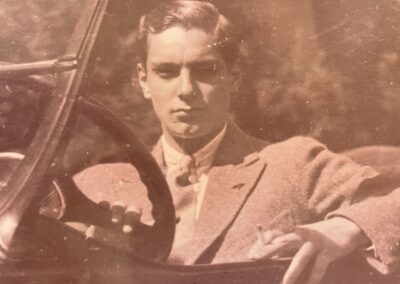

TS: Yes. My great-great-grandfather was James Stillman who led what would become Citibank. So, he was one of the big Bankers of the early 20th century, my grandfather Chauncey was his grandson, and my grandfather was born in 1907. My grandfather was somebody who

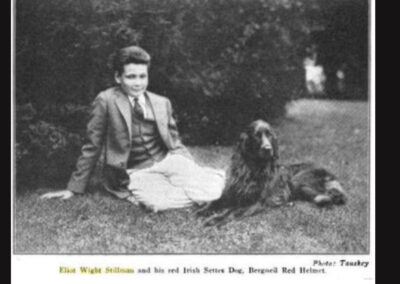

lost both parents very young. In 1925 and 1926, both of his parents died. So, he’s just a teenager. He has two siblings – Eliot and Elizabeth. So this leaves three children as the sole heirs to this fortune. And then, a year or so later, grandfather’s brother Eliot is killed in a car accident at 19. You know what we start to see is like this idea – an imagined idea about the people who built America as having everything – in air quotes – I don’t know what ‘having everything’ means – because everybody is impoverished or wealthy in different ways. So, I think that one of the things that that my grandfather took from the kind of lost that he experienced was that everybody suffers – and that building a kind of beauty that invites people in – felt important to him. But he couldn’t really say that in a certain way – and I’m not sure that he ever really did. So, he just kind of set out to do that.

HB: Before we talk about Wethersfield and how your grandfather started building this let’s set the stage a little bit what was going on nationally and globally. We know personally, he lost his parents, he lost his little brother, he lost his first child, his marriage fell apart. Lots of trauma in any person’s early life. On a national scale there had been a First World War, there had been the Great Depression, a Dust Bowl. What else informed his politics and his view of the world?

TS: The Dust Bowl was something that he was very interested in and the first Farm manager at Wethersfield was a man named Owen Boyd who had come out of the Dust Bowl – as Dust Bowl veteran. He [and grandfather] were some of the first people to start culling some of the lessons of the Dust Bowl and using them here at Wethersfield. So, my grandfather was a very, very progressive conservation leader. The the man-made Lakes were designed as kind of natural ways to irrigate a garden in a drought. Soil was a huge interest of his because he would have remembered the dust clouds that would come from the Midwest to the Northeast – terrifying. And so, Wethersfield, before it was a garden was really an experiment in how to manage land well, good land stewardship, and how to build communities. And it was an experiment that went on for decades and expressed itself in different ways at different times.

HB: The location of this place is totally weird, Tara (laughs). I mean, we are in the middle of farming country. It never occurred to me that an estate like this would exist 20 minutes from my farm. We live around all these kinds of little historic villages here in the Hudson Valley.

And I’d never even heard murmurings of this place it was such a well-kept secret. How did your grandfather arrive at this place?

TS: I think he arrived at this place because he was an avid equestrian and so he loved to ride. The Millbrook Hunt rode here – a lot. Wethersfield, when it was discovered by grandfather was

was basically two abandoned dairy farms. Everything was completely deforested; everything had been depleted. So, he could see potential – that we know would take a certain special eye to see.

HB/TS crosstalk: Imagination. Mystery. What was possible.

HB: It takes a courage. And, that vision you’re talking about. Building a community. Because when you build a place like this how many people do you employ? This place doesn’t run itself.

TS: No.

HB: And so, he knew that he would be employing laborers to build the house. There were people to work the land, to deal with the animals, to deal with the carriages – I mean that alone is a full- time gig. Your grandfather had the resources to be able to employ and a whole town of people.

TS: Yes, absolutely. And it was very important to grandfather to ensure that people who worked here were treated well.

HB: There seems to be a little bit of FDR’s New Deal – in the creation of this community out here – the creation of jobs, of opportunit. For everything your grandfather was creating, this space the house itself lacks pretentiousness. He was building a grand estate – but it is

conservative in a way that I would love for you to explain.

TS: Yes. I mean the house itself is fairly modest considering what it could be in relationship to a formal garden on this order and I think that that was a very intentional decision made to – in no way – attempt to compete with the beauty of nature. He only wanted to, sort of, fold the house into it – and then have the nature and the gardens amplified. In fact, you know, a lot of the rooms in the Garden conform to rooms within the house.

HB: It’s my favorite thing – looking out of windows in this house – and the hedges and the plantings, and the pools, and the reflections all work with the space. It’s something that is kind of common now, where you have outdoor living space – but that idea that the scope of the room as extending until you can see mountains in the distance requires so much planning.

TS: It’s a really remarkable place. I would add that one of the things that has given me time to reflect his been reading through some old letters. And one of the crushing losses of his life that we have not yet gotten into, is that after his brother Eliot died, his sister, Elizabeth died – in about 1959 or so. So, she was only in her late 40s or so. I think that he loved one when people came to visit because I think that he really wanted to have people understand something – that I think that now maybe we understand better – at least I understand it better than I did before which is there is really like something extraordinarily important about beauty in dark times. Because as we go through dark times, sometimes you go through dark times by yourself -it’s more personal. But, if there’s if there’s a large-scale crisis of some kind – an international crisis, a war, or [crosstalk HB/TS] – a pandemic …

HB: Honestly, there is no better time for us to understand what your grandfather was going through in the early years of this estate – than what we all just collectively lived through, right?

TS: Yes, absolutely. And I think that on the one hand we sort understand that nature and green spaces are really important, or we understand that families and communities are really important. But to understand that in theory – and then to understand that when you don’t have them anymore – when you can’t actually access those things? You start looking for beautiful things. Because they are like oxygen. Because if every day is just full on dark – it’s just too much. You have to find these things that just get you through – and so Wethersfield to me is that invitation to come and find what is beautiful – to anybody.

HB: If the home, a space devoid of frills and built with the intention to create jobs gives us insight into Mr. stillman’s desire for inclusion, what then can we infer from the surrounding grounds of the property?

TY: My name is Toshi Yano and I am the director of horticulture at Wethersfield Estate & Garden.

HB: Can you remember the first time you caught wind of Wethersfield?

TY: I do. My old boss Caroline Burgess, the Director of Stonecrop Gardens takes her interns on a field trip to Wethersfield every year, and the interns would always come back invariably raving about this Garden. This beautiful formal garden – and at the time I remember saying that I don’t really like formal Gardens – that they always felt sterile to me. They would always say, ‘no, no,’ this one – this one’s different.

HB: So, Wethersfield was something you’d heard about from these interns. Did you know what its reputation was in the world of gardening at the time?

TY: No. Nobody really knew about it. It was a kind of secret garden Caroline knew about. Caroline knew about it and she loved it and I think over the years, I would hear some snatches of conversation – maybe. People would speak about it in hushed tones – and, like, reverently. But not that many people did know. It was sort of this secret garden. And if you knew, you never knew what you needed to know. The garden was only open three days a week – in the afternoon and on strange days like Wednesday and Friday or something like that – and for only four months of the year. So, people didn’t really know when we would be open, how to get here.

HB: It is a long winding drive to get up here, you know and it’s almost like it’s got Speakeasy energy where you kind of have to know the password.

TY: Right – yes. And before Google Maps or something – how would you find your way to this dirt road, to this house and garden that you can’t see from the road that dirt road? So, a handful of people knew it, but I think it wasn’t a well-known Garden.

HB: So, do you remember your first trip up here?

TY: Yes, I do. It was my mother’s birthday and so we’d gone to visit a garden about a half an hour north. We had eaten lunch, and we were trying to figure out what to do with the afternoon – and I said ‘oh, you know my old boss loves this garden – it’s around here somewhere.

HB: ‘I’ll find it!’

TY: Yes! (laughs). We were with we were with my daughter too, and so we got to the top of the hill, and you know, just immediately fell in love with this this place. The first thing you see is this amazing view of the Taconic range, and then you turn and see these seemingly ancient hedges that sort of invite you to enter and so we started wandering around. My daughter was running around hiding underneath some of the topiary and finding different secret rooms.

Between the views and the hedges and the water features and the peacocks – and then this really mysterious Woodland Garden. We all just fell in love with the space.

HB: So, you come here, and you visit with your mother and your daughter. How do you begin working here?

TY: Oh, that’s great. Yes. So, at the time, I was working at a private estate and I was dying to get back to public gardening work and different things would come up but none of them seemed right. And then I was looking at a job board. And sure enough, Wethersfield was searching for a Head Gardener and I dropped everything. In my mind, it had become my favorite garden. And I said, ‘oh, how amazing would it be to work at Wethersfield’.

HB: So, this Garden is architectural. Is that typical of an Italian Renaissance Garden – walk me through what’s normal.

TY: Yes, it is. During the Renaissance, Italian Garden makers started creating super elaborate formal spaces, playing with plants in geometrical formations – sort of taking them out of the Cloisters, where they’d been behind walls – and projecting them out into the broader landscape. The plants had been protected and nurtured and now the world was opening up again. So, the garden makers would create rooms with plants. They used hedges to define spaces and they put ornaments in the rooms with ancient urns and statues that they’d find in Roman ruins. The folks that were commissioning them were Bishops and Cardinals and Popes – and the Medicis. They were sort of displays of power and the more profound and experience you could create in the garden, the more powerful you were. So that’s sort of the typical Italian Garden Italian Renaissance Garden. At Wethersfield there are some of those elements – hedges, the water features, the rooms exist – but it’s on a much more intimate scale. It’s sort of more human sized. The rooms feel like rooms in a house rather than these vast paintings of plants that one would look down upon from villa or a palace. And the house is similar too. It’s a Georgian house, but it’s not overwhelming – it’s a on a human scale.

HB: You mentioned something earlier about the Wilderness Garden. This Garden doesn’t just exist in this sunny Hilltop surrounding the house. It actually extends into lots of acreage on the property, right?

TY: It does. Yes. So Italian Renaissance Gardens, besides their formal spaces had these, sort of, darker – more mystical spaces that they called Bosci. They were often dotted with statuary – laid out along an itinerary that was meant to sort of tell a story – sometimes about civilization, sometimes about the owner of the estate. They were considered sort of mystical spaces – often pagan spaces ….

HB: Really?

TY: Yes. They would be dotted with pre-Christian statuary – Greek mythological figures – and they were sort of meant to act as a counterpart to the formal Garden. So, you would visit

the Woodland Garden first – the Bosco – and make your way through it – and then you’d get to this formal Garden it would show what humanity could accomplish when working with God.

to overcome this sort of Darker mystical Woodland Garden.

HB: What was the aha moment that you had with the Wethersfield Garden?

TY: So, as I mentioned there are these Italian precedents for the garden Bosci that were laid out allegorically. So, knowing that, I would sit in the winter months – sort of trying to figure out how these statues were related. As I mentioned, Mr. Stillman was a classicist and was well traveled, and well read. He knew the Italian Gardens and what they meant – and so I knew that these weren’t just random statues dotted around the woods. I thought – it must be journey. But I didn’t have the classical education. So, I would sit and Google things, you know. Who were these statues? How are they related? I think the biggest key – there were a few – but there was a blueprint for a set of steps that descend into the space through a couple statues designed by Mr. Stillman’s landscape architect Evelyn Poehler. On the blueprint, she calls the steps the steps to Dorcas – and I said who or what is Dorcas? And it turns out she’s a woman, a widow, in the Bible who dies and is brought back from the dead by Saint Peter. The blueprints were made in 1971. And Mr. Stillman was divorced, but his ex-wife had died in 1968 – so he was a widow too – and so I wondered is he Dorcas who has somehow died and been reborn.

Is the Wilderness his story? So, there’s this notion that the garden was maybe his personal Journey – spiritual journey. And the second key was the scavenger hunt that [Mr. Stillman] made for the property – and one of the things that he asks people to find is the entrance to Orcas. And I said, ‘well, what’s Orcas? Is it Dorcas – is this some kind of different spelling? And it turns out Orcas is a Roman deity of the underworld – and so again, themes of death, rebirth. I think I started to unlock the meaning. There’s this famous passage in Virgil’s Aeneid where the hero Aeneas is searching for his dead father, and he enters the underworld through the jaws of Orcas. There are also these creatures that inhabit the underworld – and you know Virgil mention centaurs, specifically, in the introduction to the underworld. Sure enough, one of the first statues you see after you enter the gates the entrance to Orcus is the centaur.

HB: And its massive …

TY: Yes. It’s huge. Apparently, it was carved from a 2-ton piece of stone – and so

you know – it’s got to be 15 feet tall or something like that. It’s huge.

HB: You arrived at a conclusion after learning more about Mr. Stillman and really investigating the statuary and the spaces surrounding the house and that is what?

TY: So, I think ultimately the Garden is a Dante Garden. I think Dante’s Divine Comedy gave Mr. Stillman a cosmology that allowed him a kind of optimism. Despite the death and loss that wracked his life from a very early age. I think instead of being stuck and mired in that loss, Dante allows him to use that loss as a starting point – but then to move up and out of that to a kind of paradise at the top of the hill. It’s Dante – and then it’s also Virgil because Aeneas in the Aeneid is searching for his dead father. He goes to the underworld in search of his dead father, and he ends up finding him in the Elysian Fields. Wethersfield also has an Elysian field just south of the house where there’s a field with statuary surrounding it. And at the end of the field is this Arch. That was maybe the last aha moment. There’s an inscription and Arch.

From Isaiah which says, “His eyes shall see the King in his beauty. They shall behold a land of far distances.” (Isaiah 33:17). You think when you first see it, that’s a perfect description for Wethersfield – you’re at the top of this hill and in this glorious space. But then I was doing research again about Mr. Stillman’s life and I came across this image of his little brother’s grave

Mr. Stillman had lost his little brother about a year after he had lost his father, which was a year after he lost his mother, and so he buried his brother – and on the grave was that same inscription.

You know, ‘his eyes shall see the King.’ And so, you get this sense that this this field is like a Memorial Field. And then the statues along the side of it sort of fell into place as well – they represent his parents and represent himself on the field as well. So, you know, between Virgil and Dante, I think you have you have the story of the garden.

HB: Have you always been someone who’s been drawn to Mysteries? Were you a kid that read books?

TY: Oh yes. I liked Encyclopedia Brown. I didn’t read The Hardy Boys or the Nancy Drew mysteries so much – but I loved the covers of them. They always seemed so intriguing.

HB: How much of the mystery of these Gardens at Wethersfield inspired you to want to work here?

TY: So, I love the Woodland Garden here. When I came, it was sort of the first thing I wanted to tackle because it had been neglected for decades after Mr. Stillman died. When you wander through it, you can see sort of remnants of the plantings and how beautiful it must have been – and I thought, ‘oh, you know if I could do anything in my time at Wethersfield, I would love to make the Wilderness Garden sing again’.

HB: You mentioned the Dante Garden. Are there any other Dante Gardens in the United States?

TY: Not that I know of. I think there’s only one other one that I’ve read about in the world – so it’s pretty unusual.

HB: Join us in our next episode as Toshi and Professor Joseph Luzzi take us on a tour of Chauncey Stillman’s Dark Woods of Wethersfield, as we try to understand the very personal message of this symbolic Secret Garden. Please visit our website at www.wethersfield.org.